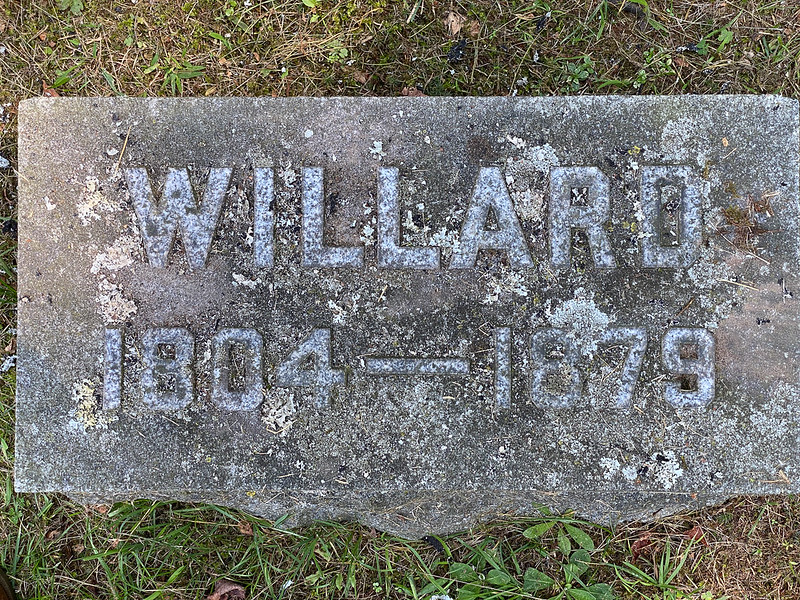

WILLARD BLANCHARD (1804-1879)

Willard Blanchard was born on October 18, 1804, in Washington, Sullivan County, New Hampshire, the fourth of thirteen children of Nehemiah and Sally Dinsmore Blanchard. Willard’s father and family moved from New Hampshire to Genesee County, New York, around 1810. There are other records showing that Willard’s father was one of the early settlers of this region and that he bought 100 acres of land east of Albion on April 16, 1816.

Nothing is known about Willard’s early life.

Willard was “articled” (i.e., sold by contract) 25 acres of his father’s 100 acres on May 28, 1828.

On June 4, 1825, Willard married Lois Smith in Brockport, Monroe County, New York. (Monroe County is the county just east of Orleans County.) Willard was 20 and Lois was 18. It’s not clear where Lois was from. Records of her birthplace are not in agreement; the choices are Vermont, Massachusetts or New York.

Willard and Lois had twelve children between 1826 and 1850. Tragically, they lost seven of their children. Three died young and four sons were lost in the Civil War, the latter all in within a four-month span in the summer of 1864. One other son was wounded in the Civil War and yet another son predeceased his father. Here’s the family:

Harriet

|

Born on

6 Jul 1826

|

Died in childhood in 1833

|

Alva Smith

|

Born on

16 Dec 1829

|

|

Clarisa

|

Born on

26 Sep 1830

|

|

Lewis Nehemiah

|

Born on

5 Nov 1832

|

Wounded at Cold Harbor and died in a hospital

in Washington, D.C., in June 1864

|

Albert

|

Born on

27 Oct 1834

|

Died in infancy in 1835

|

Orrin Lorenzo

|

Born on

10 Jul 1836

|

Wounded at Cold Harbor and died in September

1864 while on furlough in Albion

|

Daniel Densmore

|

Born on

12 Jul 1838

|

|

David C.

|

Born on

12 Jun 1840

|

Drowned in 1875

|

Lyman Porter

|

Born on

10 Jul 1842

|

Wounded at Petersburg and died in City Point,

Virginia, in June 1864

|

Cassius M.

|

Born on

27 May 1845

|

Wounded in Civil War and discharged

|

George Dwight

|

Born on

5 Mar 1847

|

Died at Petersburg in August 1864 of “black

fever” (an acute infection)

|

Electa

|

Born on

11 Oct 1850

|

Died in infancy in 1851

|

Willard was a shoemaker in Albion for 35 years. His father Nehemiah had also been a shoemaker, so it is likely that he learned the trade from him. He must have started his business around 1830, because, as you’ll read below, by 1864 he was no longer able to support his family.

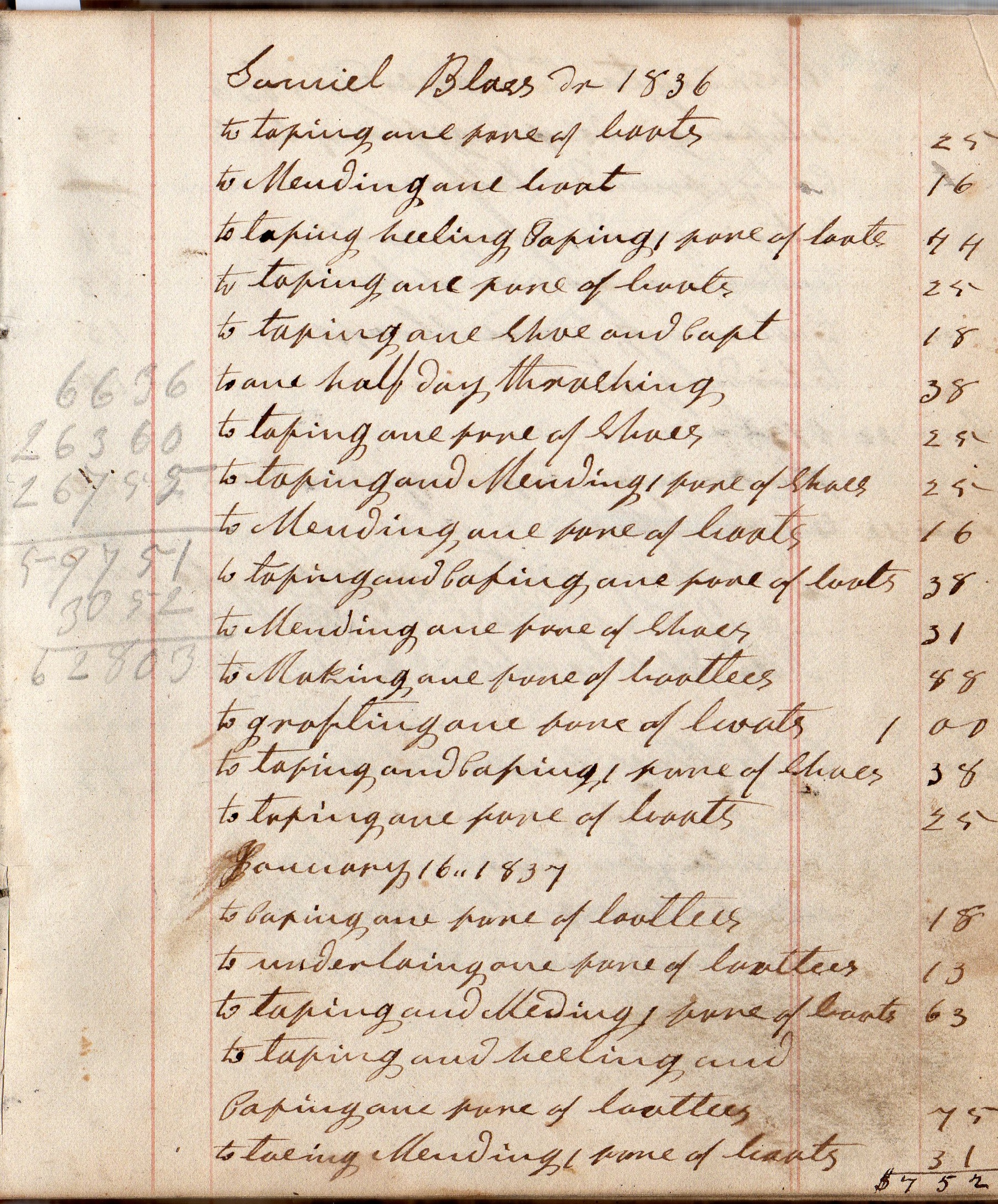

Two of Willard’s ledger books have been saved and handed down in the family. They contain information about his shoe business from around 1836 to 1848 with a few entries beyond that. The first book covers the years 1836-1843. The second book overlaps with the first; it begins with 1843. Most of the accounts in the second book end in 1848, but there are a couple of penciled-in entries from 1850 and 1851, and there are a couple of notes dated 1855 and 1857. There are also some loose sheets in the second book which contain accounts of money owed by someone for groceries and tobacco in 1867.

Willard made entries in these ledger books for the work he did for his customers. He made, sold, and repaired shoes, boots, boottees, kip boots, slips, and brogueans. The price that he charged to make one pair of boots ranged from 75 cents to $1.50 for lined boots and $2.50 for “fine” boots. One pair of shoes cost from 44 cents to 75 cents. One pair of boottees ranged in price from 63 cents to one dollar.

There were many categories of repairs in Willard's books. He tapped, capped, toed, heeled, soled, nailed, vamped, welted, underlaid, mended, and patched his customers’ boots and shoes. Prices for these services ranged from six cents for capping or mending one boot or one shoe to 75 cents for heeling or vamping one pair of boots. Willard also repaired things like harnesses, halters, bridles, and tugs, and he sold leather by the pound and ounce.

Here's a sample page from the first ledger book.

There are also pages in his book for some of his brothers and his father. Here's one for his father, Nehemiah. The entries here are for other things like potatoes, straw, tobacco and flour, not shoes. It's not clear whether these are expenses or income. There are also pages in his book for some of his brothers and his father. Here's one for his father, Nehemiah. The entries here are for other things like potatoes, straw, tobacco and flour, not shoes. It's not clear whether these are expenses or income.

These ledger books also contain entries where people owed Willard for things other than making or repairing shoes. These included things like helping with thrashing or cutting lumber.

Willard took payment in kind for the majority of his shoe making and repair work. Thus, aside from the relatively few entries in his ledger books for cash payments, he credited such goods and services (in his own spelling) as: drawing lodes of wood, digging potatoes, cradling, hoing, moing, picking up stone, digging post holes, hay, straw, corn, wheat, oats, beenes, apples, peches, potatoes, pickls, chease, butter, vinegar, flour, pork, beef, mutten, veal, taller [tallow], fat, shougar, salt, tobacco, tea, wool, bedticking, candles, solelather (sole leather), calfskin, and stove pipe joints.

The books are really quite messy. Willard scribbled calculations and made notes wherever he could find a blank space. He made notes upside down on some pages and sideways on some pages. If there was room on the page when the first year of someone’s account had passed, he would begin another entry for the same person for the next year. Sometimes the space on that page had been filled by someone else’s account, so he would start a new page elsewhere in the book. Parts of some pages have been cut out. Some pages have been cut out entirely. He evidently wrote notes to people on these pages and simply cut them out of his ledger book. A couple of them remain in the books. There are also diary-like entries (like “Mie Cow turned to paster”) scattered among the account entries. Perhaps for services rendered he grazed his cow in one of his customer’s pastures for a few days. In the second ledger book he made notes when several of his sons started at various jobs and he noted the deaths of his parents.

Here is one of the messiest pages from Willard's ledgers:

In November 1833 Willard “articled” the 25 acres of land he got from his father to a man named Samuel Bloss (for whom he did a lot of shoe repair work). In November 1848 he bought some land (parts of lots 29 and 30) in the village of Albion at the corner of Clarendon and Van Buren Streets. He paid $300 for that property, and in 1850 he bought a plot adjacent to it for $100. It is not entirely clear where he and his family lived between 1833 and 1848 or even if he had houses and in fact lived on those two lots. There is a clue, however, in a note that he wrote in one of his ledgers but didn’t tear out. It was a request for money – one dollar – from a Mr. Right [sic], and Willard signed it “Barre, Aug 2,1845.”

Some real estate and deed research still needs to be done. (After Willard died in 1879, no taxes had been paid on that second lot in East Albion, so in 1883 it was advertised by the Orleans County Treasurer and sold to one James Watt for the grand sum of $12.59!)

After their son Lyman died in the Civil War in June 1864, Willard’s wife Lois applied for what was called a mother’s pension. The primary reason she did that was because Willard was in ill health and was “unable to do but little labor.” Although he was only about 60 years old, he was described as “aged and infirm,” and he had been afflicted with a liver complaint and dyspepsia (indigestion) for about the previous 13 years (i.e., back to 1851 or so).

Lyman had actually been supporting his parents, especially his mother, ever since he was old enough to work until he enlisted in the Army in December 1863. He had bought his mother clothing, goods and groceries, and he gave her money from time to time. After he enlisted, Lyman gave his mother his entire enlistment bounty of $350 and he continued to send her money while he was in the service. Lyman wanted his mother to use this money to buy a house and a lot in Albion, which she did. That house and her and Willard’s household furniture were the only possessions they had. They had no other source of income. So Willard and Lois depended on Lyman for support in their aged and declining years, and Lyman had fully intended to take care of them.

One wonders why Willard’s and Lois’s other living children didn’t help them out in their time of need. Son Alva Smith and his wife Jane and family, daughter Clarisa and her husband Franklin Wilson and family, son Daniel and his wife Sarah and family, and son David were all living in the immediate Albion area. Could Lyman have been the only one who cared?

Lois’s application was approved and she was eligible for a pension of $8.00 per month starting the day of Lyman’s death. (Lois was apparently illiterate, by the way. She signed her “Mother’s Application for Pension” with an “X” and “her mark” was witnessed by her son-in-law and daughter, Franklin and Clarisa Wilson.)

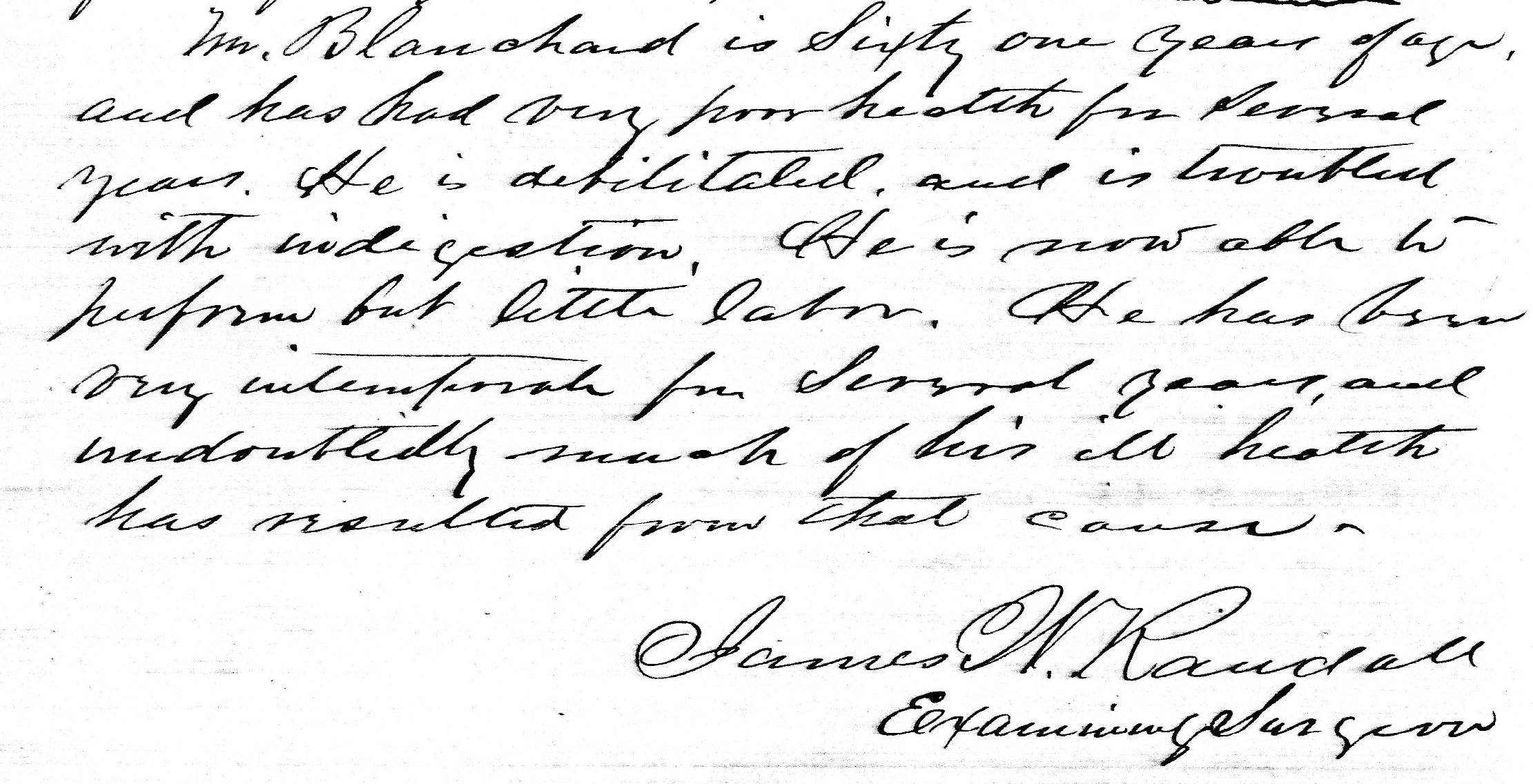

In connection with Lois’s application for a mother’s pension, a surgeon in Albion named James W. Randall examined Willard and wrote the following report dated December 11, 1865: “Mr. Blanchard is Sixty one years of age, and has had very poor health for several years. He is debilitated, and is troubled with indigestion. He is now able to perform but little labor. He has been very intemperate for several years, and undoubtedly much of his ill health had resulted from that cause.” Here's the original of Dr. Randall's report:

It’s not too difficult to understand his drinking – after losing four of his sons to the war in four months the previous year, not to mention the loss of his other three children earlier.

In 1869 the Blanchards were apparently living on Madison Street in Barre (Albion).

Willard’s wife Lois predeceased him. She died in Albion of apoplexy on March 4, 1874. She was 66 years old. Lois died without a leaving a will. In Willard’s Petition for Letters of Administration (to Alva S. Blanchard) dated March 28, 1874, it stated that, in addition to her husband, Lois had left five children (Alva S. of Clarendon, Daniel of Murray, David of Barre, Cassius of Barre and Clarisa Wilson of Holley) and three grandchildren of her deceased son Lewis. The document furthermore stated that all of Lois’s “goods, chattels and credits” did not exceed the sum of $200.00.

Another of Willard’s children died tragically before Willard himself died too. His 35-year-old son David drowned in October 1875.

In November 1876 Willard applied for an Army pension based on his son Lyman’s service. He had to attest to the facts that he was wholly or in part dependent upon his son, that he was not engaged in the rebellion, that he was not already receiving a pension, and that he hadn’t remarried since the death of his son. He was a resident of Clarendon at the time.

On March 16, 1877, Willard signed a statement that had been prepared for him. Here’s a quote from the document: “Deponent [Willard] further says he is in poor health and unable to do but very little manual labor not enough to pay his board and that his health is failing. And that he has no property or means of support except the use of a small cheap house during his life situate in said village of Albion. And that the rent of said house does not exceed two dollars per week. And is old & requires considerable repairing every year. And that the repairs for the last year has exceeded the rent on said premises.”

It appears that Willard did not live in this small house in Albion, but he rented it out at $2.00 a week. In another signed statement Willard’s son-in-law, Franklin A. Wilson, stated that the taxes, insurance and repairs on this house consumed nearly all of Willard’s yearly rent and sometimes more.

Three doctors (“surgeons”) from Rochester evidently examined Willard and filed the following report on his health on September 5, 1877: “He states that he is a shoemaker by trade & that he has not worked at his trade for the last 10 or 15 years – He was an old man at the time of his sons enlistment – We cannot state whether he was in a condition to labor or not. We have only his statement of above [regarding Lyman’s death] – He is a spare man of fair appearance of health but states that he is bilious – His age is about 73 years.”

Willard died of “dropsy” (edema) on September 18, 1879. He was 74.

(Willard’s birth date and death date have alternatively been seen as October 13, 1804, and September 19, 1879, respectively.)

Willard and Lois are buried together in the Mt. Albion Cemetery in Albion.

20210831

|

There are also pages in his book for some of his brothers and his father. Here's one for his father, Nehemiah. The entries here are for other things like potatoes, straw, tobacco and flour, not shoes. It's not clear whether these are expenses or income.

There are also pages in his book for some of his brothers and his father. Here's one for his father, Nehemiah. The entries here are for other things like potatoes, straw, tobacco and flour, not shoes. It's not clear whether these are expenses or income.