YORKE STANFORD BLANCHARD (1899-1959)

.jpg)

Yorke Stanford Blanchard was born in Holley, Orleans County, New York, on February 2, 1899. Here's a picture of the house he was born in. He was the oldest of four children of Alva Ward Blanchard and Lucy Gay Stevens Blanchard. He was  baptized at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Holley on June 16, 1901. baptized at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Holley on June 16, 1901.

No one in the family knows or remembers hearing where the names Yorke and Stanford came from. His sister Edith didn’t know when asked. Yorke is certainly an unusual first name, and Stanford is not any kind of family name. That’ll be a mystery forever.

Yorke’s father had a shop in Holley where he made machine parts and sold and repaired bicycles. Sometime in 1902, the family moved to Brooklyn, New York, where his father got involved in automobile sales.

Cars were clearly a big part of Yorke’s early life. There are several photographs of him .jpg)

just as a little kid sitting behind the wheel of a big car - like these. The photo on the left was taken at their home in Brooklyn probably around 1903-04. And the one on the right is Yorke with his kid sister Biz, probably in 1905, and presumably also in Brooklyn.

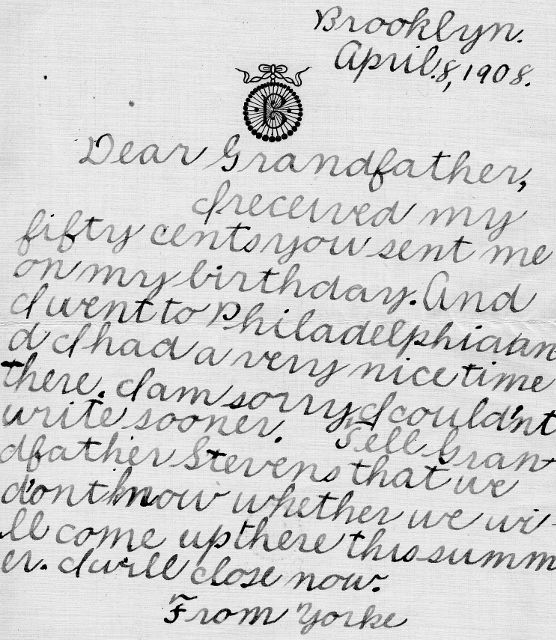

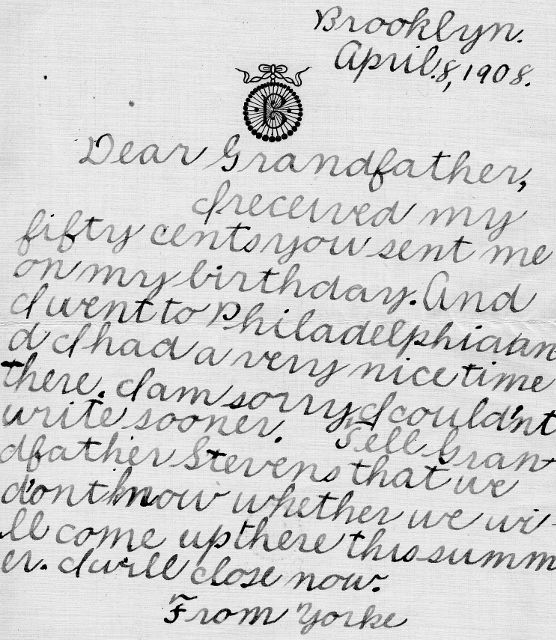

Here's a letter that Yorke wrote to his grandfather Alva Smith Blanchard in Clarendon, New York, in 1908. How about that penmanship! (Grandfather Stevens is Yorke's mother's father, John J. Stevens.)

Yorke attended elementary school at Glenwood Road School, P.S. 152, located at 725 East 23rd Street in Brooklyn. According to an account in the March 18, 1912, Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper, he and two other boys made the "8A Boys" honor roll for February 1912. In the unmarked photo below, Yorke is seated in the second row (or is it the third row?), second from the right. It's a little hard to see, but written in chalk on the board behind them - in cursive - is "6AB." It's probably safe to assume that this was the combined 6A and 6B boys class (sixth grade) at Glenwood Road School. It probably would have been taken around 1910.

Here's an enlargement of Yorke from this photo. (Compare with the photos below. Notice that ever-present unruly lock of hair on his forehead!) Here's an enlargement of Yorke from this photo. (Compare with the photos below. Notice that ever-present unruly lock of hair on his forehead!)

Yorke graduated from the eighth grade at Glenwood Road School on January 29, 1913. That was just four days before his fourteenth birthday.

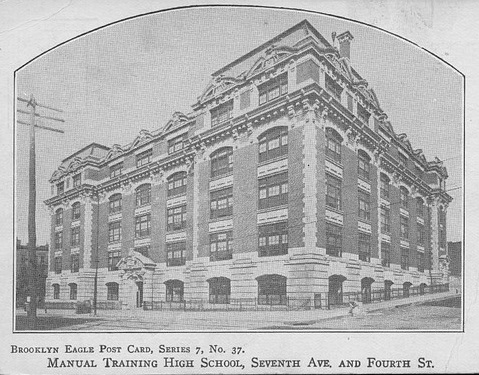

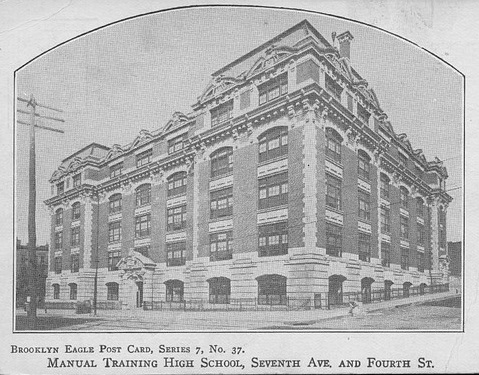

There are no surviving family records that indicate what Yorke did next, but there is plenty of convincing evidence from other sources that he attended the Manual Training High School at 237 Seventh Avenue in Brooklyn. The 1915 New York State census for Brooklyn shows Yorke's occupation as "school" at age 16, so he was obviously still a student at that time. And the 1940 U.S. census shows that he did complete three years of high school.

The Brooklyn Manual Training High School (MTHS) was apparently sort of what we used to call a vocational-technical school or a trade school, and that seems an appropriate place for Yorke to have gone, based on his mechanical aptitudes. But the school also offered academic classes. In addition to courses like carpentry, machine shop, foundry work and printing, the school also taught mathematics, chemistry, history, physics and English. And even Latin!

Here's the evidence for MTHS: In a December 7, 1916, article in the Brooklyn Times Union newspaper, it was mentined that there was a Poster Club at MTHS. Yorke had an artistic flair, so it's likely that he would have belonged to that club. The article noted that the seventh graders were anticipating a dance they had planned for the next evening, and "Yorke Blanchard deserves credit for the excellent poster which he made to advertise the function."

There were occasional accounts on the society pages of a couple of Brooklyn newspapers about high school fraternity and/or sorority dances. (Fraternities and sororities at high schools were common in those days.) Yorke's name showed up - usually misspelled as "York" - as having attended dances at the Hotel St. George that were sponsored by a fraternity called Gamma Eta Kappa. Further research shows that the Sigma Epsilon chapter of the Gamma Eta Kappa fraternity was a social club located at Manual Training High School. The newspapers indicated that Yorke attended a dance in June 1916 and another one in December 1916 and two dances in May 1917. You'll see below that Yorke served in the Army from October 1917 to March 1919, so he obviously wouldn't have shown up in the newspapers at dances during that time frame.

And more evidence: In May 1919, the Sigma Epsilon chapter of the Gamma Eta Kappa fraternity hosted a "welcome home" dance to honor its members who had returned from serving their country. York [sic] Blanchard's name was on the list of young men who attended that event. Since he was identified as a "member" of the fraternity, it seems pretty clear from this and the other evidence that he had been a student at Manual Training High School.

Then there is this intriguing photograph (on the left here) that appeared in the 1913 "Manualite," which was a yearbook of Manual Training High School. It's a close-up from a seventh grade photo of all boys, most of whose last names begin with a "B." (Curiously, some "high" schools also had seventh and eighth grades.) Unfortunately, none of the first names are given, but there is a Blanchard among the last names listed on the page where the photo appeared. And this boy here looks very much like Yorke looked as a younger lad (photo on the right). Then there is this intriguing photograph (on the left here) that appeared in the 1913 "Manualite," which was a yearbook of Manual Training High School. It's a close-up from a seventh grade photo of all boys, most of whose last names begin with a "B." (Curiously, some "high" schools also had seventh and eighth grades.) Unfortunately, none of the first names are given, but there is a Blanchard among the last names listed on the page where the photo appeared. And this boy here looks very much like Yorke looked as a younger lad (photo on the right).

But there's a problem: In 1913 Yorke would have been 14 years old - too old for seventh grade. According to a librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library who looked at all the available Manual Training High School yearbooks from 1913-1917 - there were evidently two different ones, "Manualite" and "Prospect" - there are no other mentions of the name Blanchard. Of course, his image may still be in one of those books without his name. That's something else to investigate some day. Here's a photo of Manual Training High School.

Meanwhile, Yorke’s parents had bought a farm in Millerton, Dutchess County, New York, in 1910. They used the farm as sort of a country getaway. The family would regularly go up to Millerton from Brooklyn to spend long weekends or an entire week at the farm. They would travel either by train or drive up themselves in their Pope Toledo automobile. According to entries in some of his father’s diaries, Yorke was helping out in his father’s garage at 101 Liberty Street in Brooklyn during this time. A couple of times when the family went up to Millerton, Yorke either stayed behind in Brooklyn or went back to Brooklyn ahead of the others to mind the store. He was only 15 years old at the time. And at least once in 1915, when he was 16, Yorke drove the Pope Toledo by himself from Lake Mohegan in Westchester County to Millerton.

The U.S. entered World War I in April of 1917. Later that year Yorke decided to join the Army. He enlisted in the Aviation Section of the Army Signal Corps. It looks like he didn’t tell his parents until after he had enlisted, though, because his father .jpg) made the following entry in his diary on October 29, 1917: “Yorke took a day off and sent us a telegram this evening that he had joined the colors as chauffeur in Aviation (svcs?) at Fort Slocum.” Yorke’s official date of enlistment was the next day, October 30th. made the following entry in his diary on October 29, 1917: “Yorke took a day off and sent us a telegram this evening that he had joined the colors as chauffeur in Aviation (svcs?) at Fort Slocum.” Yorke’s official date of enlistment was the next day, October 30th.

Unfortunately, only a few of Yorke’s military records remain. There was a fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis in 1973, and the records of his service that were kept there may have been destroyed. A few were available from alternate records sources.

On his Honorable Discharge form it says that when Yorke enlisted he was 18 years and 8 months old, his occupation was “chauffeur,” and he had blue eyes, dark brown hair, a ruddy complexion, and he was 5’ 7 ¼” tall. A vocation of his was “radio operator.”

He was sent first to Fort Slocum, which was located on David’s Island in Long Island Sound off the coast of New Rochelle, New York. Fort Slocum was the busiest recruiting station in the East during the war, and it probably served as just a temporary holding area in Yorke’s case. Yorke’s father visited him there on November 3rd and noted in his diary that Yorke was okay but that he would leave for Fort Sam Houston on Monday the 5th and could not get home leave. So on Sunday the 4th, the whole family – A.W., Lucy and their three other children – drove to Fort Slocum to bid Yorke goodbye. A.W.’s final words for that diary entry were “A beautiful Nov day but…”

Fort Sam Houston, in San Antonio, Texas, was a major Army training facility during World War I. It isn’t known what kind of training Yorke received at Fort Sam (perhaps some sort of basic training?) or how long he stayed there, but after that posting he was assigned to Rich Field in Waco, Texas. Yorke’s unit, the 150th Aero Squadron, had actually been established in November 1917 at Kelly Field in San Antonio but it was reassigned to Rich Field. Dozens of other squadrons were also formed at Kelly Field and then transferred to other locations because there wasn’t enough room at Kelly to house the burgeoning air service and all the recruits.

Rich Field was an Army Signal Corps Aviation Section training base that began training pilots on the Standard Aircraft Corporation J-1s in December 1917. Twenty-five J-1s had arrived at Rich Field on November 14th, and the 150th Aero Squadron uncrated the planes and set them up. Yorke may have been involved in that activity. In May 1918 the Aviation Section was renamed the Army Air Service, and the next month the Air Service switched to the Curtiss JN-4D "Jenny" as their standard training plane. Below is a photo of a cadet getting his pilot training in a Jenny that was based at Rich Field probably in 1918.

One story that came down through the family was that Yorke was an airplane mechanic on the Jenny. Presumably he would have had to receive some sort of aircraft maintenance training somewhere. But he may not have done that; he may just have been a driver. (His father did note that Yorke had enlisted as a chauffeur.) A different anecdote that got passed down was that when Yorke was stationed in Texas some higher-up asked one time if anyone knew how to drive a motorcycle. Yorke said yes, even though he had never been on one. If it had been a motorcycle with a sidecar, then it wouldn’t have been too difficult to learn how to drive. He would just have had to figure out how to shift it. Yorke may have just had some kind of desk job too. There’s no real record. One story that came down through the family was that Yorke was an airplane mechanic on the Jenny. Presumably he would have had to receive some sort of aircraft maintenance training somewhere. But he may not have done that; he may just have been a driver. (His father did note that Yorke had enlisted as a chauffeur.) A different anecdote that got passed down was that when Yorke was stationed in Texas some higher-up asked one time if anyone knew how to drive a motorcycle. Yorke said yes, even though he had never been on one. If it had been a motorcycle with a sidecar, then it wouldn’t have been too difficult to learn how to drive. He would just have had to figure out how to shift it. Yorke may have just had some kind of desk job too. There’s no real record.

There are a couple of tantalizing clues in two letters that Yorke wrote to his mother from Waco in 1918, however. On probably the 27th of March, he wrote: “We’re flying so constantly now that it is hardly possible to sneak a few minutes to write but now I’ve just a few during noon hour.” Was he flying? Probably not. Or was he supporting the flyers? Probably so.

And then this letter two weeks later, on April 11th: “There’s not much doing in camp now excepting for the fact that 60 men are leaving for St. Paul, Minn., to study Liberty motors at the Government factory. I do hope I can get to go because I believe it to be a great opportunity.” This note was written on letterhead that read: “Aviation School, Rich Field, Waco, Texas.”

There was an Aviation Mechanics’ Training School in St. Paul. That’s more in line with what is known about Yorke’s Army career. Construction of the St. Paul training facility was halted soon after Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, however, and Yorke apparently never got to go there.

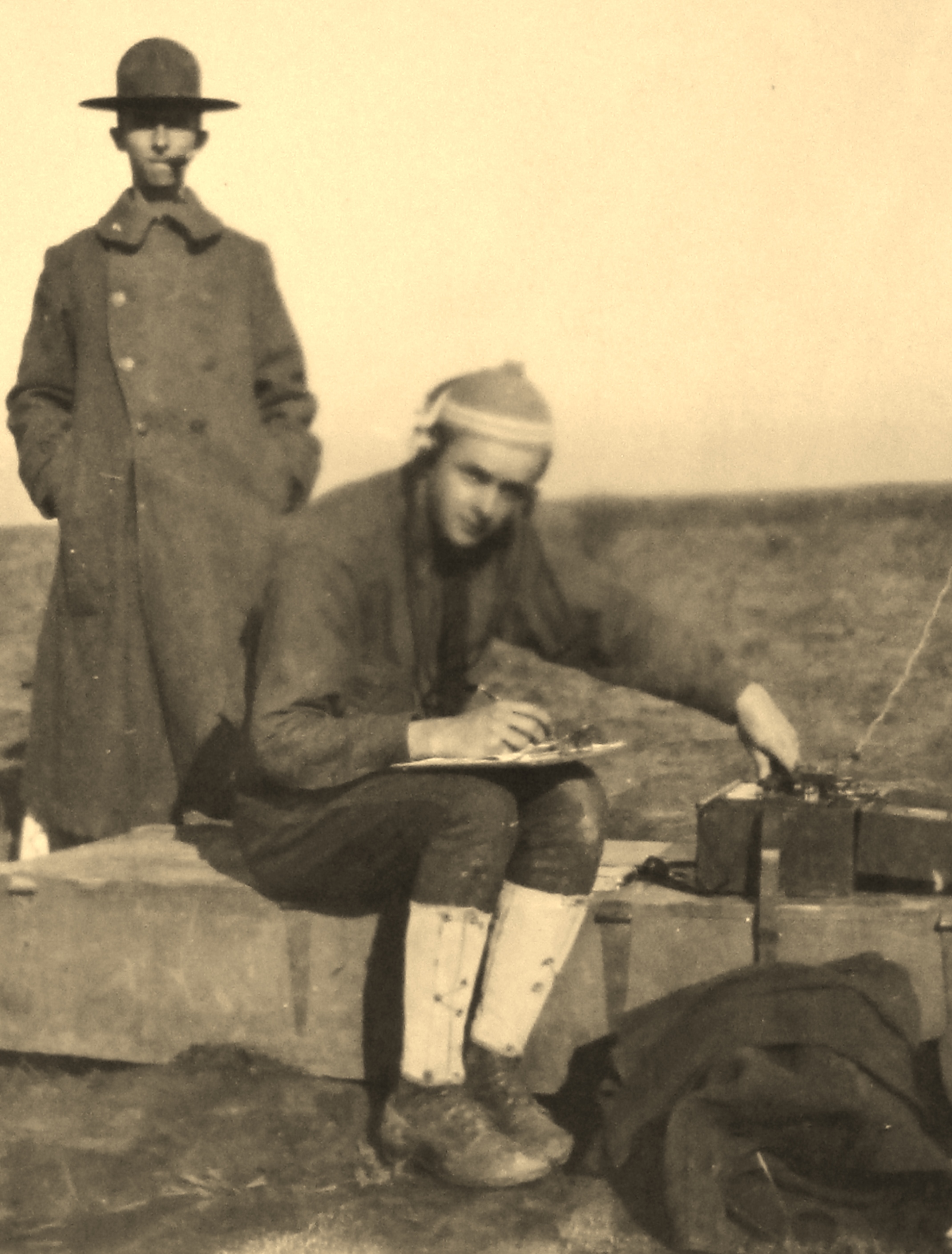

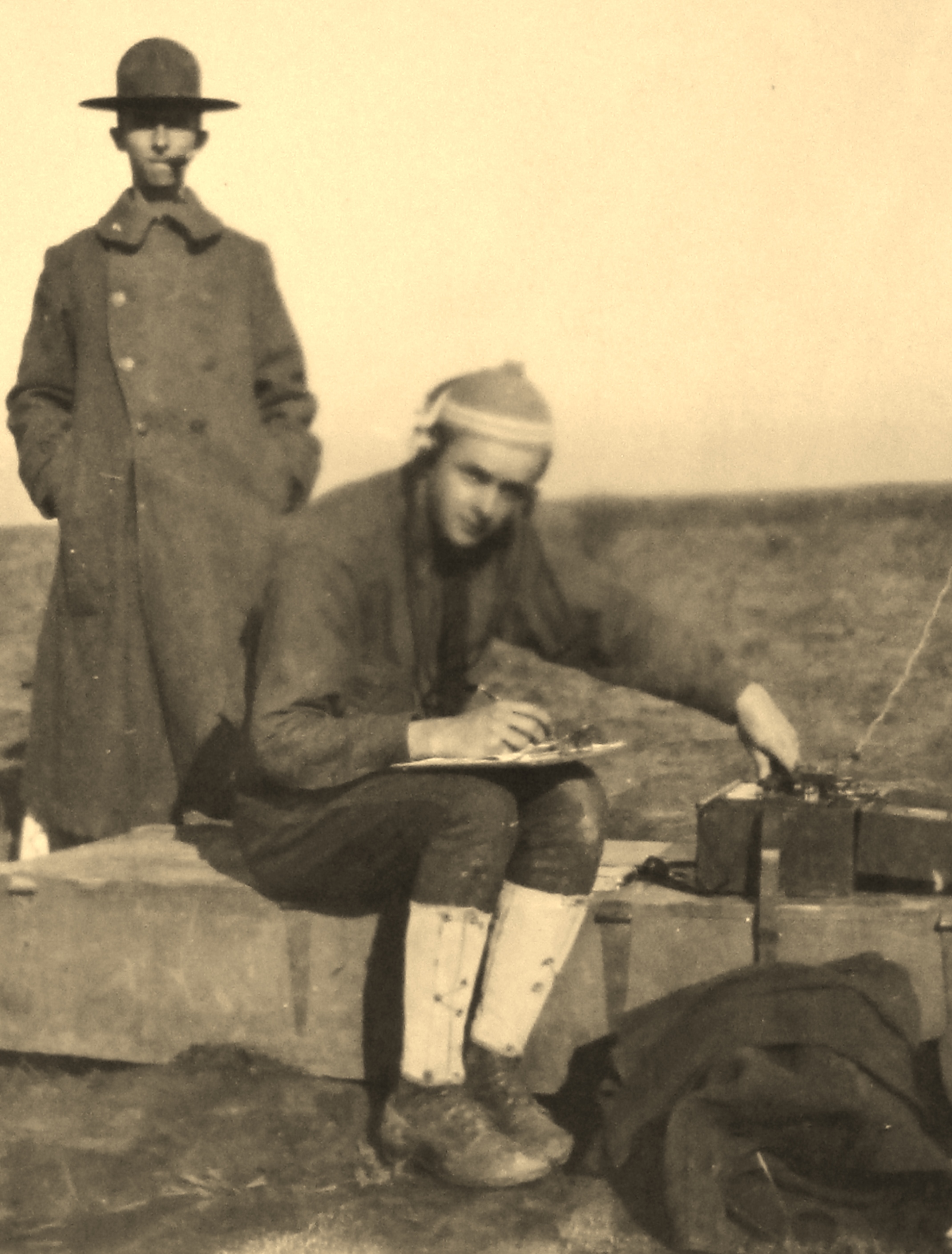

Meanwhile, Yorke’s existing military records show that on August 7, 1918, he was sent to something called S.R.O. in Austin, Texas. This was the Air Service School for Radio Operators that was set up at the University of Texas in Austin in the spring of 1918. According to a brief history of the Air Service School, "the aim of the school was to train men as quickly as possible in the science of maintaining, constructing and operating radio apparatus of the Air Service, including the wireless telephone." The following subjects were included in the students' curriculum: Elementary Electricity, Practical Radio Operation, Buzzer Practice, Artillery Co-operation, Direction Finding and Wireless Telephony. He's doing some radio stuff in the field in this photo, under the watchful eye of somebody. (By the way, Yorke's Army buddies called him "Blanch" while they were at this school.) Meanwhile, Yorke’s existing military records show that on August 7, 1918, he was sent to something called S.R.O. in Austin, Texas. This was the Air Service School for Radio Operators that was set up at the University of Texas in Austin in the spring of 1918. According to a brief history of the Air Service School, "the aim of the school was to train men as quickly as possible in the science of maintaining, constructing and operating radio apparatus of the Air Service, including the wireless telephone." The following subjects were included in the students' curriculum: Elementary Electricity, Practical Radio Operation, Buzzer Practice, Artillery Co-operation, Direction Finding and Wireless Telephony. He's doing some radio stuff in the field in this photo, under the watchful eye of somebody. (By the way, Yorke's Army buddies called him "Blanch" while they were at this school.)

From Austin Yorke went to Ellington Field in Olcott, Texas, on September 30, 1918. Ellington Field was an advanced flight training base near Houston, but there was also a radio school for training advanced radio operators there. Yorke presumably underwent some kind of additional radio training there as well. In a book called "Ellington 1918," Yorke is listed under the Radio Detachment of Squadron "C" of the 194th Aero Squadron. His category was "Unassigned (Attached to Radio Detachment for Duty)."

Yorke’s squadron, the 150th Aero Squadron, was never activated, so Yorke never got overseas during the war. In fact, he never left Texas. The 150th was demobilized when the war ended on November 11, 1918. This photo of Yorke was taken on Armistice Day, somewhere in Texas. Yorke’s squadron, the 150th Aero Squadron, was never activated, so Yorke never got overseas during the war. In fact, he never left Texas. The 150th was demobilized when the war ended on November 11, 1918. This photo of Yorke was taken on Armistice Day, somewhere in Texas.

After the armistice Yorke stayed in the Army a short while longer and was discharged at Ellington Field on March 5, 1919, with the rank of private. His organization at discharge was noted on a form as “Co. C, Detached AS(A).” AS(A) probably expands to “Air Service (Army).” Yorke had only served a little over sixteen months.

The Blanchard family moved around a lot during those years they lived in Brooklyn and the surrounding area. In 1918 and 1919 the family was living in Port Washington in Nassau County on Long Island. The 1920 U.S. census, taken in January, also showed Yorke living with his parents in Port Washington, and his occupation was listed as “Draftsman, (two words illegible).”

Later in 1920 the family moved permanently to their 110-acre farm in Millerton. Yorke’s parents had named the farm “Cluyvala,” which was a transposition of their names, Lucy and Alva.

Yorke’s younger sister, Edith (“Eacy”), once said that Yorke used to play the banjo. She remembered him sitting on the porch at Cluyvala and strumming the banjo. That might have been the same banjo that Yorke’s father had in the early 1890s. There's a banjo barely visible on top of the piano in this photo of Yorke and his sister Biz at their home on 20 Waldorf Court in Brooklyn. It was probably taken around 1904.

Sometime in the next year or so Yorke got a job as an auto mechanic at MacArthur’s Garage in Millerton. The garage was located in a building on Main Street just west of the Presbyterian Church. There was a gas pump in front and a ramp that went down to the basement where the repairs were done. Sometime in the next year or so Yorke got a job as an auto mechanic at MacArthur’s Garage in Millerton. The garage was located in a building on Main Street just west of the Presbyterian Church. There was a gas pump in front and a ramp that went down to the basement where the repairs were done.

While he was working at MacArthur’s Yorke met a young lady named Margaret Bard whose family had just moved to Millerton in 1919. Margie, as she was known (that’s Margie with a hard “g”), was still in high school at the time. She had seen Yorke around town. Yorke’s other younger sister, Biz, was in school with Margie, and Margie knew her. Yorke and Margie finally formally met at a fireman’s dance in Lakeville, just across the state line in Connecticut. (All his dancing experience in his high school days in Brooklyn must have served him well for this encounter!) Margie said that Yorke didn’t mix much with the locals, and at first she thought he was “kind of a stuck-up city toff [a dandy],” as she put it, but she realized it was because he was pretty shy. While he was working at MacArthur’s Yorke met a young lady named Margaret Bard whose family had just moved to Millerton in 1919. Margie, as she was known (that’s Margie with a hard “g”), was still in high school at the time. She had seen Yorke around town. Yorke’s other younger sister, Biz, was in school with Margie, and Margie knew her. Yorke and Margie finally formally met at a fireman’s dance in Lakeville, just across the state line in Connecticut. (All his dancing experience in his high school days in Brooklyn must have served him well for this encounter!) Margie said that Yorke didn’t mix much with the locals, and at first she thought he was “kind of a stuck-up city toff [a dandy],” as she put it, but she realized it was because he was pretty shy.

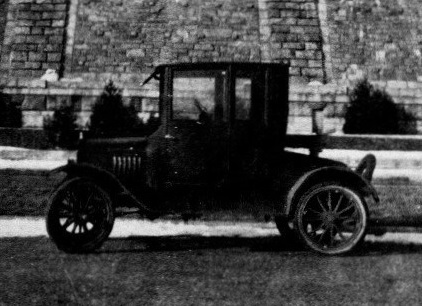

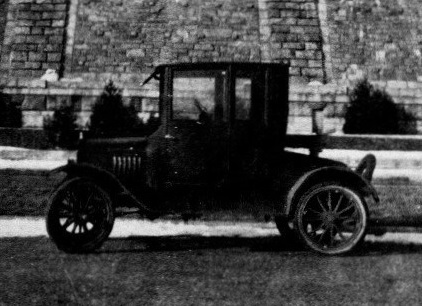

After Margie graduated from high school, she headed off to normal school in New Paltz, across the Hudson River, for two years. Yorke occasionally drove her back from New Paltz to Millerton. And after Margie finished at New Paltz in 1923, she got a job teaching fourth grade in at the West Side School in Pleasantville, in Westchester County, New York, where her family had come from. Yorke would go down to visit her nearly every Sunday. They would have dinner with some of Margie’s relatives there, and then Yorke would drive back  to Millerton. At first Yorke drove a car that he had made himself. It had a tin body, no roof, and it only seated two. Margie and Yorke referred to this car as the “Doodlebug.” Later Yorke got a little Chevrolet coupe that had a roof. They called this car “Coupie.” Here's a photo of "Coupie." to Millerton. At first Yorke drove a car that he had made himself. It had a tin body, no roof, and it only seated two. Margie and Yorke referred to this car as the “Doodlebug.” Later Yorke got a little Chevrolet coupe that had a roof. They called this car “Coupie.” Here's a photo of "Coupie."

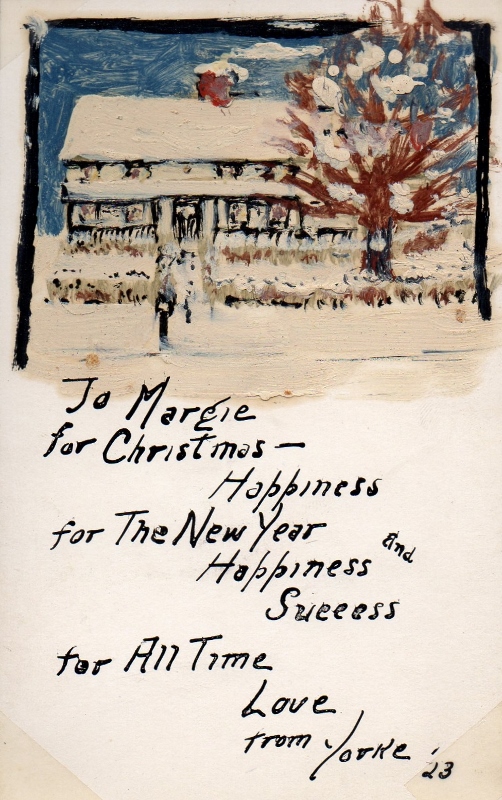

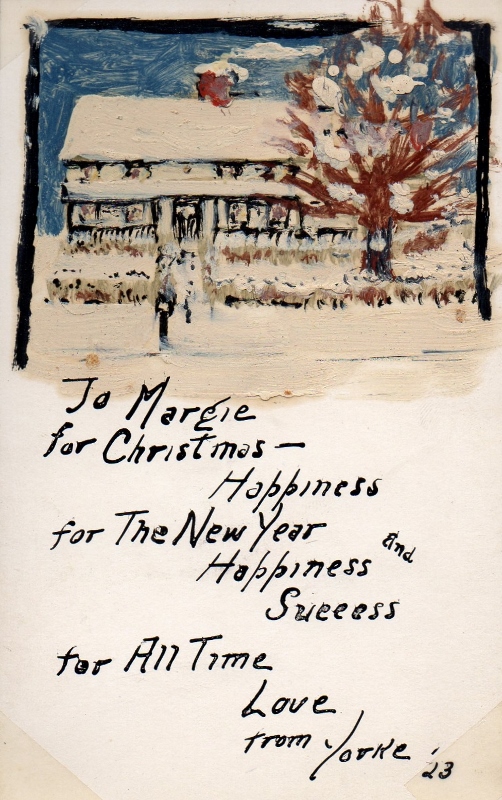

In 1923 Yorke hand-painted this Christmas card for Margie. It was a depiction of the Bard farm in Millerton. He painted a couple of others too. In 1923 Yorke hand-painted this Christmas card for Margie. It was a depiction of the Bard farm in Millerton. He painted a couple of others too.

Margie only lasted one year at her teaching job in Pleasantville. She hated it and realized she wasn’t cut out to be a teacher. So she ended up back in Millerton. This was in the spring of 1924. Margie’s mother died unexpectedly on July 2nd of that year. Yorke went over and lived at the Bard farm in Millerton with Margie, her father and her sister, Connie. (The Bard farm was located at State Line. Everyone always said the farm was in Millerton, but it was actually just across the line in Salisbury, Connecticut.)

Three weeks later, on July 26th, Yorke and Margie were married at the Presbyterian manse in Millerton. Yorke was 25 and Margie was 19. Very sneakily, they had told everyone that they would be going to Albany for their honeymoon, but they went to New York City instead. They posed for this honeymoon picture at Coney Island on the 27th. They started a scrapbook on their wedding day, which  they kept up for a couple of years. They took turns making entries. About their wedding night at the Hotel Pennsylvania, Yorke wrote: “After an interruption by the maid to turn down the bed and provide fresh towels we hung out the little sign that you see on the page before [it was the hotel’s “Do Not Disturb” sign]. At eleven o’clock the light was put out and we turned in.” At the bottom of that page he added another note: “Of course Yorke had left his razor and tooth brush home and had to buy new.” they kept up for a couple of years. They took turns making entries. About their wedding night at the Hotel Pennsylvania, Yorke wrote: “After an interruption by the maid to turn down the bed and provide fresh towels we hung out the little sign that you see on the page before [it was the hotel’s “Do Not Disturb” sign]. At eleven o’clock the light was put out and we turned in.” At the bottom of that page he added another note: “Of course Yorke had left his razor and tooth brush home and had to buy new.”

By January 1925 Yorke was working at a different garage in Millerton, the Dutchess Auto and Supply Company. On the 19th of that month Yorke was sent down to Tarrytown for a week to attend the Chevrolet Service School.

After going through another, used Chevrolet coupe in late 1924, Yorke and Margie bought a brand new 1925 Chevrolet coupe in April 1925. It was only the second such car in Millerton and they were very proud of it. They called this one “Coupie III.” They had to drive 20 miles an hour for the first 500 miles to break in the engine, so they took little rides every evening.

If Yorke went to Tarrytown to learn how to service Chevrolets, it looks like he didn’t get much chance to practice what he learned back at Dutchess Auto. There are two slightly conflicting stories – both from Yorke – about what he did later that year. According to what he wrote in his and Margie’s wedding diary, he was .jpg) promoted to the job of stock clerk at Dutchess Auto in August of 1925. But in a disability insurance application form that he filled out the next month in September, Yorke indicated that his duties were “Salesman. Salesroom duties only.” Maybe stock clerk and salesman were pretty much the same job. (Also noted on his application: He was making $150 a month and he weighed 145 pounds and was 5’ 10” in height.) promoted to the job of stock clerk at Dutchess Auto in August of 1925. But in a disability insurance application form that he filled out the next month in September, Yorke indicated that his duties were “Salesman. Salesroom duties only.” Maybe stock clerk and salesman were pretty much the same job. (Also noted on his application: He was making $150 a month and he weighed 145 pounds and was 5’ 10” in height.)

Yorke was one of the charter members of American Legion Post #178 when it was formed in Millerton in September 1927. He served as commander of the post at one time (in the early 1930s), and he also did a stint as Adjutant of the Dutchess County American Legion. Margie joined the post’s American Legion Auxiliary in 1929. She served at one time as president of the Auxiliary. Both remained Legion members for many years.

Yorke’s political affiliation is unknown. In a 1932 Poughkeepsie, New York, newspaper article about local Republican and Democratic delegations going to their respective state conventions, Yorke's name showed up as having been appointed one of about fifteen "sub-county committee chairmen" of the "Non-Partisan Independent Veterans committee of Donovan-for-Governor." Colonel William Donovan was the candidate for governor likely to be supported by Dutchess County Republicans. (He lost.) In her later life, Margie was a staunch Republican, so maybe Yorke was too.

Yorke repaired radios on the side. He had envelopes printed up that said “Authorized Silver-Marshall Service Station. Yorke S. Blanchard, Millerton, New York.” The Silver-Marshall company manufactured radios from 1924 to 1933, so Yorke probably did that sometime along in there. He built his own radio that he had in his house on Dutchess Avenue. It had a black round dial and was mounted in a piece of dark-stained plywood that was about two feet wide and more than a foot high. The radio slid into a shelf in a built-in bookcase (which he probably also built) to the left of the fireplace. The speaker for that radio was a separate unit. It was a furniture-like case with turned wood corners and a heavy upholstery cover over the speaker.

Yorke and Margie’s first child, Elizabeth Gay, was born on March 29, 1928, at Sharon Hospital in Sharon, Connecticut. Her name was always spelled Elizabeth later, but on her birth certificate, it’s Elisabeth. Yorke and Margie called her Betty.

In 1929, Margie started keeping a daily diary of her own. She only entered a couple of lines each day, just a summary of what she did or what happened, but she kept the diary up faithfully for the next 69-plus years. So she provided a lot of first-hand insight into what the Blanchards did for all those years of their marriage.

Yorke was still working at Dutchess Auto in 1929. There’s a 1929 photo of all the Dutchess Auto employees, and Yorke is in it (along with his father A.W. and his sister Biz). Also in 1929, in December, he finished making a magazine stand for his father. This was probably intended to be a birthday present, since his father’s birthday was January 13th. Yorke made some other things that are still in the family in addition to that magazine stand: a copper butter dish, a copper wall candle holder, oak candle holders, and oak cutting boards with handles made out of bent copper tubing.

Yorke and Margie had bought a lot on Dutchess Avenue in Millerton for $1,000 and built a six-room house on it. The house set them back $6,000. In 1930 they moved out of the Bard farm and into the new house. Margie’s father and sister Connie remained at the Bard farm at State Line. (The house on Dutchess Avenue didn’t have a street number back then, but now it’s # 46. This photo was taken in 1955, after the mulberry tree had split from the heavy snow, but the looks of the house hadn't changed much.) Yorke and Margie had bought a lot on Dutchess Avenue in Millerton for $1,000 and built a six-room house on it. The house set them back $6,000. In 1930 they moved out of the Bard farm and into the new house. Margie’s father and sister Connie remained at the Bard farm at State Line. (The house on Dutchess Avenue didn’t have a street number back then, but now it’s # 46. This photo was taken in 1955, after the mulberry tree had split from the heavy snow, but the looks of the house hadn't changed much.)

On July 11, 1932, Yorke lost his job at Dutchess Auto. This was probably due in some way to the Great Depression. The following January, he landed a civil service job as an RFD mail carrier in Millerton. He started out just as a “relief,” filling in when one of the regular carriers was sick or something.

Along in here Yorke also worked at the auto shop that his father had opened up in his former cider mill on South Mill Street in Millerton. In August and September of 1932, two ads appeared in the Millerton News for "Blanchard Service" on Mill Street in Millerton. Blanchard Service advertised itself as a machine shop that did auto and radio repairing and welding. And the name attached to those first two ads was Yorke S. Blanchard. Frequent additional ads for Blanchard Service ran in the newspaper until October 1933, but Yorke's name didn't appear in any more of them. It is likely that this may have been a joint effort between Yorke and his father, A.W. Blanchard. The radio repair claim certainly sounds like Yorke. The machine shop claim sounds like A.W. He ran a similar shop back in his younger days in Holley, New York. The services they provided included rebuilding cars, tune-ups, batteries, parts, oil and lube jobs, flushing auto cooling systems, even "grinding ensilage cutter blades." That sounds more like A.W. too, from his experience selling cars and running a garage in Brooklyn (and being the son of a farmer).

Blanchard Service also sold cars. It was reported in the local newspaper that in June 1933 they sold a Hupmobile, and in July 1933 they sold a "new custom eight Auburn sedan," both to local customers. They were obviously still in business in 1934 and 1935. In September 1934 Yorke's father became the authorized Hupmobile dealer "in this territory," and the headquarters of his new Hupmobile agency was "the Blanchard's service station on Mill St."

And then in April and May of 1935 two ads appeared in the Poughkeepsie Eagle-News for the Norge Rollator Refrigerator. Unexpectedly, one of the dealers who sold them was Blanchard's Service in Millerton. It's unclear whether Yorke was still associated with the business at that time.

Yorke started delivering mail on a permanent basis to the outlying areas around Millerton on June 30, 1933, although his official appointment as a rural carrier for the Millerton Post Office was not effective until September 16th of that year. So his father probably continued to run Blanchard Service, and Yorke might have become a part-timer.

Yorke used a Model A Ford for the mail delivery. The Model A was good for that, because it sat higher and stood up better on the rutted, dirt roads around Millerton. Yorke removed the front bench seat and installed a “taxi” seat, which was a bucket seat just for the driver. That left room to his right for the mail bags. In fact, Yorke usually had two Model As – one to use for the mail route and the other one for parts. Those cars took a lot of abuse and wore out very fast! Later he used a Willys station wagon for his mail route. He also tried using a couple of other cars, but they couldn’t stand up to the washboard roads – a 1949 Buick Roadmaster, a nineteen-fifty-something German car called a Borgward and a pickup truck.

In the mornings, Yorke would park behind the post office, sort his mail and then stack it in big brown leather bags in the order of delivery – actually, in the reverse order of delivery, so the first mail to be delivered was on top. Before heading out, however, he and Ronald “Juddie” Silvernale, one of Yorke’s close friends and the fellow who had the other rural mail route in Millerton, would often stop in at Dominick’s, a bar right next door to the post office, and have a quick drink before  they headed out. Yorke’s route only required him to drive about 35 miles, so, weather permitting, he would be done in the early afternoons. Sometimes in the wintertime the weather didn’t permit, however, and he would occasionally get stuck in deep snowdrifts and have to dig out and put chains on. This photo of one of his cars taken sometime in the 1930s shows how high the snow can get on the sides of the roads in Millerton. they headed out. Yorke’s route only required him to drive about 35 miles, so, weather permitting, he would be done in the early afternoons. Sometimes in the wintertime the weather didn’t permit, however, and he would occasionally get stuck in deep snowdrifts and have to dig out and put chains on. This photo of one of his cars taken sometime in the 1930s shows how high the snow can get on the sides of the roads in Millerton.

By the fall of 1934 Yorke and Margie had realized that there were problems with their daughter Betty’s development. Betty’s IQ was measured at 54 in 1937. They had looked at a number of boarding schools for mentally retarded children around New York State where Betty could be better taken care of and provided with a specialized education. They visited facilities in Yorktown Heights, Edmeston, Rome, Syracuse and Newark (all state schools or similar facilities across New York State). Betty spent some time at the so-called (before we had political correctness) Otsego School for Backward Children in Edmeston in 1935-1937. Margie and Yorke tried but were unable to get her admitted to any of the other state schools, so they decided to enroll her in third grade at the local Millerton public elementary school in the fall of 1938 after keeping her at home since the previous Christmas. That didn’t work out either; Betty turned out to be too disruptive. So, finally, in August 1941 they made the heart-wrenching decision to have Betty institutionalized at Wassaic State School in Wassaic, New York. She was only 13 years old. She never lived at home again, except for short visits. In 1975 many of the mentally retarded residents at Wassaic State School were de-institutionalized, and accommodations were found for them in group homes in the community. Betty moved around to a variety of homes in the Dutchess County area after that. After a lengthy stay in a nursing home in Pawling, New York, Betty died of cancer on January 26, 2014, at age 85.

In 1935 Margie agreed to work for her uncle Elmer LeRoy Ryer. Uncle Roy was an ophthalmologist in Hawthorne, New York. Margie was always very close to her Uncle Roy and Aunt Flo. She said they were like second parents to her. Roy’s wife, Florence Taylor Ryer, had died in June of 1935, so perhaps Roy had asked Margie to come down and keep house for him for a while so he could tend to his practice. Or he may have actually given her some sort of office job to do. Shortly after moving down to Hawthorne, Margie wrote in her diary: “Well, I’ve been two weeks at my new job, and I like it a lot, if it weren’t for being separated from Yorke.” (That does sound more like a real job than just keeping house. We’ll probably never know.) At any rate, she and Yorke packed up their house, and Margie spent from October of 1935 to October of 1936 with her uncle in Hawthorne. (Roy later took in a long-time family friend, Laura Ver Planck, as his permanent housekeeper.) While Margie was gone, she and Yorke rented their house in Millerton to a newlywed couple who would later become their next-door neighbors. Yorke evidently moved back in with his folks at Cluyvala Farm for the year.

In September of 1937 Yorke launched a boat that he had built himself in Lakeville Lake. Lakeville is just east of Millerton, across the state line in Connecticut. At the same time he also had built a chicken coop in the back yard of their home on Dutchess Avenue and started keeping chickens. Rabbits were another part of the Blanchard menagerie later on. And there was usually a good-sized vegetable garden out behind the house. Their so-called “victory garden” was one half corn, one quarter potatoes, and one quarter other vegetables, rotated every year. They kept the potatoes in a fruit cellar that Yorke had built in a crawl space off the basement of their house. There were also two or three rhubarb plants that provided stewed rhubarb for dinner. There was a strawberry patch that wasn’t too successful and a grape arbor with four different varieties of grape, but only the Concord grapes did well. Two crabapple trees were productive too. Margie canned tomatoes and other vegetables from the garden and she made grape jelly and crabapple jelly. They were put away on shelves in the basement for the winter.

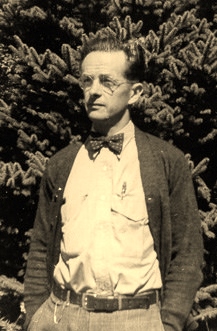

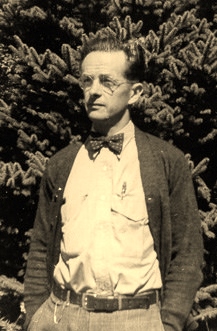

In April of 1938 Yorke started doing what was called “checking” at some of the local movie theaters, such as Amenia, Pine Plains and Lakeville. According to the Internet, this practice is still going on. Checkers are hired to visit selected theaters and do things like count the number of patrons and collect box office information. Sometimes they announce themselves to the theater manager. Other times they arrive unannounced to do what is called “blind checking.” Yorke did both until at least 1941. It’s unclear how in the world he would have found a job like that. Here's a photo of Yorke that was taken in 1938. In April of 1938 Yorke started doing what was called “checking” at some of the local movie theaters, such as Amenia, Pine Plains and Lakeville. According to the Internet, this practice is still going on. Checkers are hired to visit selected theaters and do things like count the number of patrons and collect box office information. Sometimes they announce themselves to the theater manager. Other times they arrive unannounced to do what is called “blind checking.” Yorke did both until at least 1941. It’s unclear how in the world he would have found a job like that. Here's a photo of Yorke that was taken in 1938.

On February 4, 1941, Yorke and Margie’s second child, son John Stevens, was born at Sharon Hospital. Steve attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, married Shirley Bowler in 1962, and had a successful career in the computer field in California and Massachusetts.

One of Yorke’s friends in Millerton was Oliver “Stubby” Valentine. Stubby was the local undertaker and had a monument works business. In April of 1941 Yorke went with Stubby to Vermont for a week to learn how to engrave lettering on granite gravestones. In May Yorke started working off and on for Valentine’s Monument Works on an ad hoc basis and he continued doing that for most of the rest of his life.

.jpg) Yorke was a pretty avid sportsman – a hunter and fisherman, that is, not a baseball or football fan. This photo was taken around 1953. He supported the National Wildlife Federation and started collecting their annual wildlife art stamps when they inaugurated their stamp program in 1938. He dutifully mounted the stamps in their respective albums. Yorke was a pretty avid sportsman – a hunter and fisherman, that is, not a baseball or football fan. This photo was taken around 1953. He supported the National Wildlife Federation and started collecting their annual wildlife art stamps when they inaugurated their stamp program in 1938. He dutifully mounted the stamps in their respective albums.

Yorke was one of the organizers of the Millerton Rod and Gun Club. The club was established in 1941, and Yorke served as secretary of the club for all of the rest of the 1940s and into the early 1950s. He wrote a really nice little weekly column about local hunting and fishing and about the gun club’s meetings and activities for the Harlem Valley Times, a local newspaper published just down the road from Millerton in Amenia.

Two mounted whitetail deer heads adorned the walls of the Blanchard residence on Dutchess Avenue for many years. Here's one of them over the mantle in the living room. The other one was just a little spike-horn buck. And there was a stuffed ring-necked pheasant perched on top of the china cabinet. Yorke was a lifetime member of the NRA and read their American Rifleman magazine. That was back when the NRA was strictly a sportsman’s organization and before it came to be scorned and reviled by so many.

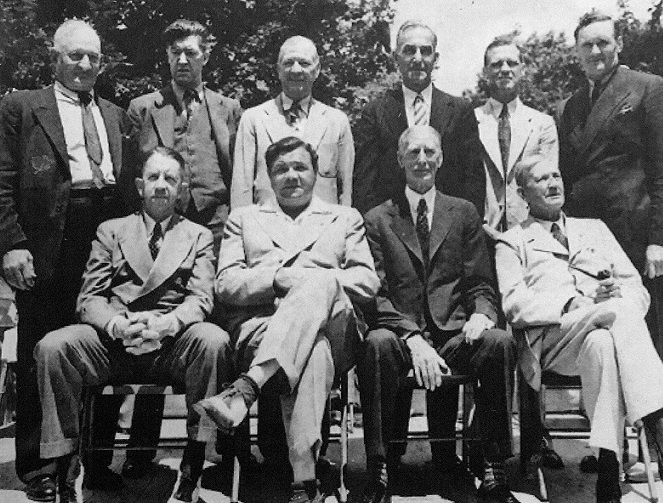

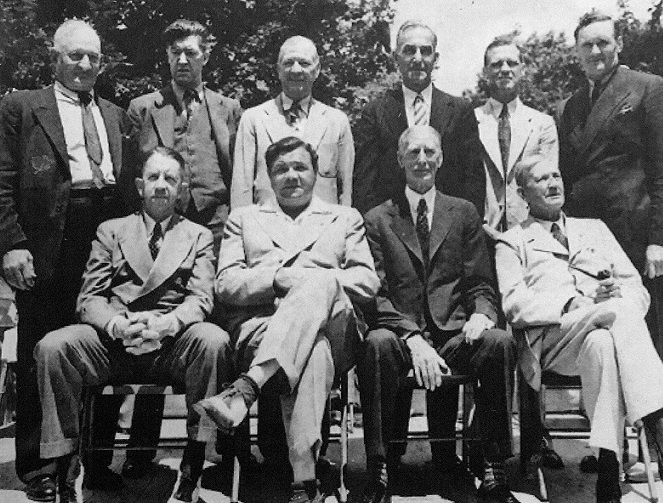

An interesting sidelight to the Millerton Gun Club story during the early part of Yorke’s tenure as a member and officer is that Babe Ruth was also a member of the club in the mid 1940s. He joined in 1945 and was an active member in 1946 and 1947 whenever he was in town. An article found on the Internet says that Ruth had a girlfriend who lived near the Millerton Rod and Gun Club. He loved to hunt and he occasionally shot trap. He spent a lot of weekends in Millerton and he would shoot at the gun club and go deer hunting with some of the local men. (He probably frequently bent his elbow with gun club members too.) Ruth's main connection in town was Yorke’s future brother-in-law, Francis LeRoy Ganung. Roy had met Ruth in New York City, and he was the one who brought Ruth to Millerton. (Roy was married to his first wife Eva when Ruth used to visit Millerton, but after Eva died in 1950, Roy married Yorke’s sister, Biz.) It is not known how well Yorke knew the Babe himself, but he certainly must have.

We're getting a little farther off-topic here, but there's another possible reason for Babe Ruth's knowledge of and interest in Millerton. The fellow sitting to Ruth's right in this photo of baseball hall of famers taken in 1939 is Eddie Collins. Eddie was a Millerton native son, born there in 1887. He played as a second baseman in Major League Baseball from 1906 to 1930 for the Philadelphia Athletics and the Chicago White Sox. He obviously knew Ruth as well as some of the other famous names in baseball. (For you baseball fans who are reading this: From left to right in the front row: Eddie Collins, Babe Ruth, Connie Mack and Cy Young. From left to right in the back row: Honus Wagner, Pete Alexander, Tris Speaker, Nap Lajoie, George Sisler and Walter Johnson.)

Yorke and some of his friends would go to a cabin or camp in the woods up on Mount Riga (they called it Mount Raggy) near Millerton for a couple of days in the fall during deer season to go deer hunting. Yorke also used to go ice fishing with some  of his friends at Indian Lake. And he used take his boys fishing at Rudd Pond on summer evenings during the 1950s. He would rent a rowboat and he would row around the lake while Jim and Steve trolled for crappies and perch or cast lures for bass and pickerel. of his friends at Indian Lake. And he used take his boys fishing at Rudd Pond on summer evenings during the 1950s. He would rent a rowboat and he would row around the lake while Jim and Steve trolled for crappies and perch or cast lures for bass and pickerel.

Aside from hunting, Yorke enjoyed competitive target shooting. And he was pretty good at it, too. He usually scored among the top couple of shooters. He participated in many shooting matches at the gun club in Millerton and elsewhere around Dutchess County. In the late 1940s, Yorke evidently spent a lot of time at the Gun Club – all day Sundays and several evenings during the week. Margie often seemed pretty miffed about this in her diary entries, writing things like “Yorke at some rifle shoot somewhere” or something like that.

Speaking of hunting and fishing, Yorke was a big fan the L.L. Bean Company. He always had a pair of the Bean boots – or the Maine Hunting Shoes, as they were called then – and he wore the chamois shirts in the wintertime. He wore heavy-duty canvas hunting pants that he also probably got from Bean’s.

During the war years, the Millerton Fire Department decided to start a first aid squad. Yorke was one of the three founding members of the Millerton Fire Department's Rescue Squad, which was established in 1942. Yorke had been a member of the Millerton Fire Department since about 1933 and had worked his way up to assistant chief by 1940.

Yorke took up gunsmithing as another avocation on the side. He worked on guns for folks around the area. Both in their house on Dutchess Avenue and later in the one on Maple Avenue he had a workshop well equipped with power tools for this work. He had a bench grinder, a Montgomery Ward metal turning lathe and a Craftsman drill press. Most of the work he did was mounting telescopic sights on rifles. That involved cutting slots in the top of the barrel for the telescope mounts. He had a jig for the drill press that turned it into a little milling machine, which he used to cut the slots in the gun barrels. He also had plenty of hand tools, including some specialized chisels and files for his gun work. He carved at least one gunstock from a crude blank of wood, most likely walnut. He did the intricate crosshatching on the grips with tools called gunstock checkering tools. He probably also did checkering on plain stocks for his customers.

Margie made entries in her diary in 1942 about some things that Yorke did as part of the war effort. He took some sort of “defense classes” in Pine Plains, and after that he would occasionally spend the night – all night long – on duty at the fire house (in Millerton). During the war years, 1941-1945, members of the Millerton Fire Department were on 24-hour alert at the fire house, with each fireman taking his turn at sleeping in. A cot and blankets were purchased and a room was set up in the fire house. Evidently the department's Rescue Squad members were called upon to do this as well, and Yorke fulfilled this obligation about twice a month.

Margie made a couple of cryptic entries in her diary, first on March 29, 1942: “Yorke went to Poughkeepsie to report at employment bureau about his questionnaire,” and then on February 9, 1943: “Hurriedly went to Poughkeepsie as Yorke had to report to U.S. Employment Bureau.” The significance of these is unknown. In April and May of 1943 she wrote that Yorke worked evenings in Amenia – from 6:30 p.m. to 1:30 a.m. – “on defense work.” Another mystery.

Yorke had a long association with the local school district. One of the earliest mentions - as clerk - was in a local newspaper in 1943. In 1949 Yorke was appointed clerk (or secretary) of the Millerton Union free school district Board of Education. He delivered the mail in the mornings for the Post Office and worked at the school in the afternoons. He got paid $600 per year for the school job.

Yorke and Margie’s third child, son James Yorke, was born on December 3, 1943, also at Sharon Hospital. Jim was married twice, first to Maureen Nichols – that marriage ended in divorce – and then to Joan Bartkowicz. He served in the Air Force Security Service, attended the State University of New York at Albany, and then spent the rest of his career at the National Security Agency in Maryland.

In 1945 Yorke got a hunting dog and named him Skippy. It was an English setter. Skippy lived in a doghouse in the backyard. That beloved dog died in 1957.

At least in 1949 and later Yorke helped out with the local Boy Scout Troop in Millerton, Troop 43, the Apache Troop. There are indications in some of the local newspapers that Yorke had been involved with the Boy Scouts - as a fundraiser - even as far back as 1932. Both of his boys, Steve and Jim, were members of the Flaming Arrow Patrol of that troop, as Cub Scouts and as Boy Scouts.

Yorke had been raised in the Episcopalian religion. But sometime in the 1920s or ‘30s his parents became interested in Christian Science and switched. Yorke didn’t follow suit. He had been married in the Presbyterian manse in 1924. In April 1950, after Margie probably talked him into it, he joined the Millerton Presbyterian Church. Margie had been attending the church regularly since 1945 and she joined it herself in 1949.

In the early 1950s Yorke did occasional surveying work for his father. A.W. Blanchard owned land in Millerton and in the Town of Northeast, and a lot of it hadn’t been properly surveyed. In the early 1950s Yorke did occasional surveying work for his father. A.W. Blanchard owned land in Millerton and in the Town of Northeast, and a lot of it hadn’t been properly surveyed.

Yorke gave his family their first television set as a Christmas present in 1954.

From around August 15th to 20th, 1955, Yorke and Margie and family took what may have been their first and only real vacation since they were first married. They took a grand tour of New York State. They visited the Thousand Islands and possibly Niagara Falls. They stopped in to see Yorke’s uncle Judd Blanchard and cousins in Batavia, and they also visited his cousin Kirk Wilcox in Grand Isle, Vermont, in Lake Champlain.

In March 1956 Yorke and Margie sold their house on Dutchess Avenue for $10,000 and paid $12,000 to buy the house at 26 Maple Avenue that Yorke’s father and mother had been living in. (As the result of a house numbering system change, probably in accordance with a county Emergency 9-1-1 law enacted in 2000, the address for this house is now 14 South Maple Avenue.) Yorke and Margie moved in in April, and A.W. and Lucy moved to a  different house in Millerton. This photo of the house was taken in 1956, and Yorke and Margie used the image on their Christmas card that year. Twenty-six Maple Avenue was a huge, old 11-room house with plenty of space for two families, but only the four of them - Yorke, Margie and the two boys - lived in it. But not for long; son Steve would leave for college in September 1958. different house in Millerton. This photo of the house was taken in 1956, and Yorke and Margie used the image on their Christmas card that year. Twenty-six Maple Avenue was a huge, old 11-room house with plenty of space for two families, but only the four of them - Yorke, Margie and the two boys - lived in it. But not for long; son Steve would leave for college in September 1958.

Sometime in the early 1950s the Millerton, Amenia and Wassaic schools centralized into the Webutuck Central School District. As of early 1954, Yorke took on the job of clerk of the new school district. In May 1957 he was offered a full-time clerk’s position at the new Webutuck Central School at $5,500, and he started that job on July 1st. But this was not a civil service job. A couple of months earlier, in March, he had interviewed for the job of business manager at the new central school district. In February 1958 he took the state civil service exam in Poughkeepsie, and on July 2nd the school board appointed him business manager at a salary of $6,000. Yorke’s last day on his mail route was July 5th, but his resignation was actually effective August 30th. His salary had been $5,021. He started his new job at the school on July 7th.

So Yorke had been delivering mail in Millerton for 26 years. He hated to give up the mail carrier job, because it was a good, steady job, and if he had stayed with it long enough, he would have gotten a pension. But, on the other hand, he ran through cars like nobody’s business. One about every year, Margie wrote. He and Margie were always paying for a car. So he decided to give up the mail job and take the school job full time.

Yorke had been a cigarette smoker since he was a young man. Camels. Unfiltered. It was an entirely acceptable thing to do in those days. As Christmas presents his boys would give him a carton of Camels. In early May 1959 Yorke had a chest x-ray at a mobile x-ray clinic that Margie happened to be volunteering at. On May 20th, the family doctor, Dr. Josephine Evarts, came over with an x-ray that showed a shadow on Yorke’s lung. It was serious. A little over a week later, on the 29th, he had his cancerous right lung removed at Columbia Memorial Hospital in Hudson, New York.

In July 1959 Yorke and a couple of other people got awards as representatives of the Town of Northeast’s “Civil Defense Auxiliary Police of Zone No. 2.” It’s not clear exactly what that was all about. Yorke had served as secretary of the Millerton Unit of Auxiliary Police, but the dates of that service are not known. In 1951 he and three other men were appointed assistant civil defense deputies by the Dutchess County Deputy of Civil Defense.

.jpg) After the lung cancer surgery at the end of May, Yorke felt well enough to return to work at the school half days, but that quickly became too much for him. His condition deteriorated over the summer of 1959. The surgery hadn’t gotten all of the cancer. Yorke remained at home, and Margie cared for him to the end. He was taken by ambulance to Sharon Hospital during the day on October 18th and he died that evening at 6 p.m. He was only 60 years old. This photo of him was taken 1958, not too long before his death. After the lung cancer surgery at the end of May, Yorke felt well enough to return to work at the school half days, but that quickly became too much for him. His condition deteriorated over the summer of 1959. The surgery hadn’t gotten all of the cancer. Yorke remained at home, and Margie cared for him to the end. He was taken by ambulance to Sharon Hospital during the day on October 18th and he died that evening at 6 p.m. He was only 60 years old. This photo of him was taken 1958, not too long before his death.

Yorke is buried in Irondale Cemetery in Millerton, near the gravesite of his parents, A.W. and Lucy Blanchard. As you drive into the cemetery from New York State Route 22, the Blanchard plot is the first one you see.

This is his military marker at his grave site.

After son Jim graduated from high school and went away to college in 1961, Margie sold the big house on Maple Avenue and moved into a small apartment in Millerton. In 1975 she married a widower named Walter Rawlins whom she had met in Florida when she visited family there. They moved to Waynesboro, Tennessee, where he had lived. Walter died in 1985, and Margie moved back north, finally settling in Millerton again, where she really felt at home. After a long life of quite good health, she suffered a series of strokes in early 1998 and died at a nursing home in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, on February 19, 2000. She was 95 years old. She is buried next to Yorke in Irondale Cemetery in Millerton. After son Jim graduated from high school and went away to college in 1961, Margie sold the big house on Maple Avenue and moved into a small apartment in Millerton. In 1975 she married a widower named Walter Rawlins whom she had met in Florida when she visited family there. They moved to Waynesboro, Tennessee, where he had lived. Walter died in 1985, and Margie moved back north, finally settling in Millerton again, where she really felt at home. After a long life of quite good health, she suffered a series of strokes in early 1998 and died at a nursing home in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, on February 19, 2000. She was 95 years old. She is buried next to Yorke in Irondale Cemetery in Millerton.

20230520

|

.jpg)

baptized at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Holley on June 16, 1901.

baptized at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Holley on June 16, 1901. .jpg)

Here's an enlargement of Yorke from this photo. (Compare with the photos below. Notice that ever-present unruly lock of hair on his forehead!)

Here's an enlargement of Yorke from this photo. (Compare with the photos below. Notice that ever-present unruly lock of hair on his forehead!)

Then there is this intriguing photograph (on the left here) that appeared in the 1913 "Manualite," which was a yearbook of Manual Training High School. It's a close-up from a seventh grade photo of all boys, most of whose last names begin with a "B." (Curiously, some "high" schools also had seventh and eighth grades.) Unfortunately, none of the first names are given, but there

Then there is this intriguing photograph (on the left here) that appeared in the 1913 "Manualite," which was a yearbook of Manual Training High School. It's a close-up from a seventh grade photo of all boys, most of whose last names begin with a "B." (Curiously, some "high" schools also had seventh and eighth grades.) Unfortunately, none of the first names are given, but there

.jpg) made the following entry in his diary on October 29, 1917: “Yorke took a day off and sent us a telegram this evening that he had joined the colors as chauffeur in Aviation (svcs?) at Fort Slocum.” Yorke’s official date of enlistment was the next day, October 30th.

made the following entry in his diary on October 29, 1917: “Yorke took a day off and sent us a telegram this evening that he had joined the colors as chauffeur in Aviation (svcs?) at Fort Slocum.” Yorke’s official date of enlistment was the next day, October 30th.  One story that came down through the family was that Yorke was an airplane mechanic on the Jenny. Presumably he would have had to receive some sort of aircraft maintenance training somewhere. But he may not have done that; he may just have been a driver. (His father did note that Yorke had enlisted as a chauffeur.) A different

One story that came down through the family was that Yorke was an airplane mechanic on the Jenny. Presumably he would have had to receive some sort of aircraft maintenance training somewhere. But he may not have done that; he may just have been a driver. (His father did note that Yorke had enlisted as a chauffeur.) A different  Meanwhile, Yorke’s existing military records show that on August 7, 1918, he was sent to something called S.R.O. in Austin, Texas. This was the Air Service School for Radio Operators that was set up at the University of Texas in Austin in the spring of 1918. According to a brief history of the Air Service School, "the aim of the school was to train men as quickly as possible in the science of maintaining, constructing and operating radio apparatus of the Air Service, including the wireless telephone." The following subjects were included in the students' curriculum: Elementary Electricity, Practical Radio Operation, Buzzer Practice, Artillery Co-operation, Direction Finding and Wireless Telephony. He's doing some radio stuff in the field in this photo, under the watchful eye of somebody. (By the way, Yorke's Army buddies called him "Blanch" while they were at this school.)

Meanwhile, Yorke’s existing military records show that on August 7, 1918, he was sent to something called S.R.O. in Austin, Texas. This was the Air Service School for Radio Operators that was set up at the University of Texas in Austin in the spring of 1918. According to a brief history of the Air Service School, "the aim of the school was to train men as quickly as possible in the science of maintaining, constructing and operating radio apparatus of the Air Service, including the wireless telephone." The following subjects were included in the students' curriculum: Elementary Electricity, Practical Radio Operation, Buzzer Practice, Artillery Co-operation, Direction Finding and Wireless Telephony. He's doing some radio stuff in the field in this photo, under the watchful eye of somebody. (By the way, Yorke's Army buddies called him "Blanch" while they were at this school.) Yorke’s squadron, the 150th Aero Squadron, was never activated, so Yorke never got overseas during the war. In fact, he never left Texas. The 150th was demobilized when the war ended on November 11, 1918. This photo of Yorke was taken on Armistice Day, somewhere in Texas.

Yorke’s squadron, the 150th Aero Squadron, was never activated, so Yorke never got overseas during the war. In fact, he never left Texas. The 150th was demobilized when the war ended on November 11, 1918. This photo of Yorke was taken on Armistice Day, somewhere in Texas. Sometime in the next year or so Yorke got a job as an auto mechanic at MacArthur’s Garage in Millerton. The garage was located in a building on Main Street just west of the Presbyterian Church. There was a gas pump in front and a ramp that went down to the basement where the repairs were done.

Sometime in the next year or so Yorke got a job as an auto mechanic at MacArthur’s Garage in Millerton. The garage was located in a building on Main Street just west of the Presbyterian Church. There was a gas pump in front and a ramp that went down to the basement where the repairs were done.  While he was working at MacArthur’s Yorke met a young lady named Margaret Bard whose family had just moved to Millerton in 1919. Margie, as she was known (that’s Margie with a hard “g”), was still in high school at the time. She had seen Yorke around town. Yorke’s other younger sister, Biz, was in school with Margie, and Margie knew her. Yorke and Margie finally formally met at a fireman’s dance in Lakeville, just across the state line in Connecticut. (All his dancing experience in his high school days in Brooklyn must have served him well for this encounter!) Margie said that Yorke didn’t mix much with the locals, and at first she thought he was “kind of a stuck-up city toff [a dandy],” as she put it, but she realized it was because he was pretty shy.

While he was working at MacArthur’s Yorke met a young lady named Margaret Bard whose family had just moved to Millerton in 1919. Margie, as she was known (that’s Margie with a hard “g”), was still in high school at the time. She had seen Yorke around town. Yorke’s other younger sister, Biz, was in school with Margie, and Margie knew her. Yorke and Margie finally formally met at a fireman’s dance in Lakeville, just across the state line in Connecticut. (All his dancing experience in his high school days in Brooklyn must have served him well for this encounter!) Margie said that Yorke didn’t mix much with the locals, and at first she thought he was “kind of a stuck-up city toff [a dandy],” as she put it, but she realized it was because he was pretty shy. to Millerton. At first Yorke drove a car that he had made himself. It had a tin body, no roof, and it only seated two. Margie and Yorke referred to this car as the “Doodlebug.” Later Yorke got a little Chevrolet coupe that had a roof. They called this car “Coupie.” Here's a photo of "Coupie."

to Millerton. At first Yorke drove a car that he had made himself. It had a tin body, no roof, and it only seated two. Margie and Yorke referred to this car as the “Doodlebug.” Later Yorke got a little Chevrolet coupe that had a roof. They called this car “Coupie.” Here's a photo of "Coupie." In 1923 Yorke hand-painted this Christmas card for Margie. It was a depiction of the Bard farm in Millerton. He painted a couple of others too.

In 1923 Yorke hand-painted this Christmas card for Margie. It was a depiction of the Bard farm in Millerton. He painted a couple of others too. they kept up for a couple of years. They took turns making entries. About their wedding night at the Hotel Pennsylvania, Yorke wrote: “After an interruption by the maid to turn down the bed and provide fresh towels we hung out the little sign that you see on the page before [it was the hotel’s “Do Not Disturb” sign]. At eleven o’clock the light was put out and we turned in.” At the bottom of that page he added another note: “Of course Yorke had left his razor and tooth brush home and had to buy new.”

they kept up for a couple of years. They took turns making entries. About their wedding night at the Hotel Pennsylvania, Yorke wrote: “After an interruption by the maid to turn down the bed and provide fresh towels we hung out the little sign that you see on the page before [it was the hotel’s “Do Not Disturb” sign]. At eleven o’clock the light was put out and we turned in.” At the bottom of that page he added another note: “Of course Yorke had left his razor and tooth brush home and had to buy new.”.jpg) promoted to the job of stock clerk at Dutchess Auto in August of 1925. But in a disability insurance application form that he filled out the next month in September, Yorke indicated that his duties were “Salesman. Salesroom duties only.” Maybe stock clerk and salesman were pretty much the same job. (Also noted on his application: He was making $150 a month and he weighed 145 pounds and was 5’ 10” in height.)

promoted to the job of stock clerk at Dutchess Auto in August of 1925. But in a disability insurance application form that he filled out the next month in September, Yorke indicated that his duties were “Salesman. Salesroom duties only.” Maybe stock clerk and salesman were pretty much the same job. (Also noted on his application: He was making $150 a month and he weighed 145 pounds and was 5’ 10” in height.)  Yorke and Margie had bought a lot on Dutchess Avenue in Millerton for $1,000 and built a six-room house on it. The house set them back $6,000. In 1930 they moved out of the Bard farm and into the new house. Margie’s father and sister Connie remained at the Bard farm at State Line. (The house on Dutchess Avenue didn’t have a street number back then, but now it’s # 46. This photo was taken in 1955, after the mulberry tree had split from the heavy snow, but the looks of the house hadn't changed much.)

Yorke and Margie had bought a lot on Dutchess Avenue in Millerton for $1,000 and built a six-room house on it. The house set them back $6,000. In 1930 they moved out of the Bard farm and into the new house. Margie’s father and sister Connie remained at the Bard farm at State Line. (The house on Dutchess Avenue didn’t have a street number back then, but now it’s # 46. This photo was taken in 1955, after the mulberry tree had split from the heavy snow, but the looks of the house hadn't changed much.) they headed out. Yorke’s route only required him to drive about 35 miles, so, weather permitting, he would be done in the early afternoons. Sometimes in the wintertime the weather didn’t permit, however, and he would occasionally get stuck in deep snowdrifts and have to dig out and put chains on. This photo of one of his cars taken sometime in the 1930s shows how high the snow can get on the sides of the roads in Millerton.

they headed out. Yorke’s route only required him to drive about 35 miles, so, weather permitting, he would be done in the early afternoons. Sometimes in the wintertime the weather didn’t permit, however, and he would occasionally get stuck in deep snowdrifts and have to dig out and put chains on. This photo of one of his cars taken sometime in the 1930s shows how high the snow can get on the sides of the roads in Millerton. In April of 1938 Yorke started doing what was called “checking” at some of the local movie theaters, such as Amenia, Pine Plains and Lakeville. According to the Internet, this practice is still going on. Checkers are hired to visit selected theaters and do things like count the number of patrons and collect box office information. Sometimes they announce themselves to the theater manager. Other times they arrive unannounced to do what is called “blind checking.” Yorke did both until at least 1941. It’s unclear how in the world he would have found a job like that. Here's a photo of Yorke that was taken in 1938.

In April of 1938 Yorke started doing what was called “checking” at some of the local movie theaters, such as Amenia, Pine Plains and Lakeville. According to the Internet, this practice is still going on. Checkers are hired to visit selected theaters and do things like count the number of patrons and collect box office information. Sometimes they announce themselves to the theater manager. Other times they arrive unannounced to do what is called “blind checking.” Yorke did both until at least 1941. It’s unclear how in the world he would have found a job like that. Here's a photo of Yorke that was taken in 1938..jpg) Yorke was a pretty avid sportsman – a hunter and fisherman, that is, not a baseball or football fan. This photo was taken around 1953. He supported the National Wildlife Federation and started collecting their annual wildlife art stamps when they inaugurated their stamp program in 1938. He dutifully mounted the stamps in their respective albums.

Yorke was a pretty avid sportsman – a hunter and fisherman, that is, not a baseball or football fan. This photo was taken around 1953. He supported the National Wildlife Federation and started collecting their annual wildlife art stamps when they inaugurated their stamp program in 1938. He dutifully mounted the stamps in their respective albums.

of his friends at Indian Lake. And he used take his boys fishing at Rudd Pond on summer evenings during the 1950s. He would rent a rowboat and he would row around the lake while Jim and Steve trolled for crappies and perch or cast lures for bass and pickerel.

of his friends at Indian Lake. And he used take his boys fishing at Rudd Pond on summer evenings during the 1950s. He would rent a rowboat and he would row around the lake while Jim and Steve trolled for crappies and perch or cast lures for bass and pickerel. In the early 1950s Yorke did occasional surveying work for his father. A.W. Blanchard owned land in Millerton and in the Town of Northeast, and a lot of it hadn’t been properly surveyed.

In the early 1950s Yorke did occasional surveying work for his father. A.W. Blanchard owned land in Millerton and in the Town of Northeast, and a lot of it hadn’t been properly surveyed. different house in Millerton. This photo of the house was taken in 1956, and Yorke and Margie used the image on their Christmas card that year. Twenty-six Maple Avenue was a huge, old 11-room house with plenty of space for two families, but only the four of them - Yorke, Margie and the two boys - lived in it. But not for long; son Steve would leave for college in September 1958.

different house in Millerton. This photo of the house was taken in 1956, and Yorke and Margie used the image on their Christmas card that year. Twenty-six Maple Avenue was a huge, old 11-room house with plenty of space for two families, but only the four of them - Yorke, Margie and the two boys - lived in it. But not for long; son Steve would leave for college in September 1958..jpg) After the lung cancer surgery at the end of May, Yorke felt well enough to return to work at the school half days, but that quickly became too much for him. His condition deteriorated over the summer of 1959. The surgery hadn’t gotten all of the cancer. Yorke remained at home, and Margie cared for him to the end. He was taken by ambulance to Sharon Hospital during the day on October 18th and he died that evening at 6 p.m. He was only 60 years old. This photo of him was taken 1958, not too long before his death.

After the lung cancer surgery at the end of May, Yorke felt well enough to return to work at the school half days, but that quickly became too much for him. His condition deteriorated over the summer of 1959. The surgery hadn’t gotten all of the cancer. Yorke remained at home, and Margie cared for him to the end. He was taken by ambulance to Sharon Hospital during the day on October 18th and he died that evening at 6 p.m. He was only 60 years old. This photo of him was taken 1958, not too long before his death. After son Jim graduated from high school and went away to college in 1961, Margie sold the big house on Maple Avenue and moved into a small apartment in Millerton. In 1975 she married a widower named Walter Rawlins whom she had met in Florida when she visited family there. They moved to Waynesboro, Tennessee, where he had lived. Walter died in 1985, and Margie moved back north, finally settling in Millerton again, where she really felt at home. After a long life of quite good health, she suffered a series of strokes in early 1998 and died at a nursing home in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, on February 19, 2000. She was 95 years old. She is buried next to Yorke in Irondale Cemetery in Millerton.

After son Jim graduated from high school and went away to college in 1961, Margie sold the big house on Maple Avenue and moved into a small apartment in Millerton. In 1975 she married a widower named Walter Rawlins whom she had met in Florida when she visited family there. They moved to Waynesboro, Tennessee, where he had lived. Walter died in 1985, and Margie moved back north, finally settling in Millerton again, where she really felt at home. After a long life of quite good health, she suffered a series of strokes in early 1998 and died at a nursing home in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, on February 19, 2000. She was 95 years old. She is buried next to Yorke in Irondale Cemetery in Millerton.